This post is also available in:

![]() Español

Español

Growing up in Colombia in the 80’s and 90’s meant being part of a divided and injured society, heir to the injustices and hatreds described in the chapter about my father; but in addition to the above, it meant witnessing the growth of the phenomenon of drug trafficking, which in its obscene clandestine profitability has fueled all manifestations of criminality: guerrilla, paramilitary, common and organized crime. The drug business has also been like a cancer that metastasized into almost all levels of society. Politics, commerce, culture and even religion were infiltrated by the corrupting money of drug trafficking, meaning that very few Colombians have not had some direct or indirect relationship with this illegal phenomenon.

This involvement began for many families with one of their members accepting an offer of illicit work with the promise of immediate fortune. Politicians would receive money to promote laws that benefited the narcos, public officials would do so to issue documents, licenses, permits, etc. The poorest, already accustomed to violence in the streets, would be employed, first as errand boys, then as guards and many eventually as hitmen. In the middle class, thanks to their higher level of education, the narcos recruited young people to operate the production chain: packing drugs, recruiting mules[1] or tallying wads of money.

My family was no exception. Several of my father’s nephews – already adults when I was a child – fell to the promises of quick riches and were able to enjoy them for a few years before they met their deaths in much the same way as most other poor people who believed they could beat poverty down the road of white powder.

Despite the above, my sisters and I never had any contact with the part of the family that got involved in shady deals. My father decided to stay away and prevent us from having access to the luxuries and ostentation that might have influenced the way we saw the world. Similarly, being well aware of the many dangers that roamed the streets, especially in a poor neighborhood such as the one we lived in, our parents generally discouraged the prospect of going out and playing with other children. Thus, the world in which I grew up was isolated from the reality of my country at the time.

The Invisible War

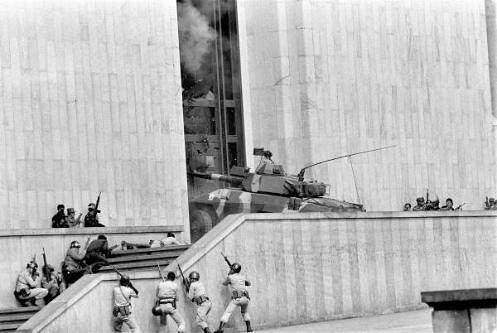

The first time I remember being aware of an incident of violence was in November of 1985. The evening news showed images of a huge building in flames with a battle tank breaking through the main gate as soldiers barricaded themselves in various places in the plaza in front. It was the Palace of Justice, taken over by the M19 guerrillas with the support of the cartel of Medellín and destroyed by the National Army in a retaking operation that has been described by many as a holocaust.

The episode was all the more memorable because a cousin of mine who was serving in the Military Police, was designated to stand guard just a few blocks from the scene. I remember excerpts from his account of the events as he made one of his frequent visits to my mother. It was the first time I remember feeling that a bloody event, one in which about 100 people lost their lives, had not just been a distant story, but a real, near event. As I listened to my cousin tell his experience, I, at only 5 years old, thought that this mysterious phenomenon of dying could also happen to someone close to me.

This new awareness that, just as there were evil beings on television, in real life there was evil as well, grew stronger as the war of the cartel in Medellin intensified. Pablo Escobar had declared war on the Colombian state to push for the dismantling of the extradition treaty with the United States, and the strategy he had chosen to apply pressure on the government was to cause terror in the population. During the eighties and until his rigged surrender to justice in 1991, Escobar executed multiple assassinations, of which the only thing I remember were the images of shot bodies, generally in a car; which were constantly featured in the news. But what had the greatest effect on the lives of ordinary Colombians during that time were the bloody and indiscriminate terrorist attacks that, starting in 1988, covered in blood the streets of Bogotá and Medellín.

When I was nine years old, I was in school doing my first grade of high school and I participated in a couple of drills for a terrorist attack evacuation, but in spite of that, I was still oblivious to the state of anxiety that many adults experienced just by going out on the street. This changed for me the following year. I saw a dead body for the first time, a victim of violence. I also became a victim of the crime that most affects the daily life of Bogota’s people:

Petty crime

In 1990, I was studying in a public school located in the south of Bogotá, in an area known for the presence of youth gangs and drug dealers. During the hours when students entered and left teh school, the movement of about two thousand students created a feeling of relative safety. However, that year my parents enrolled me in the preparation for my first communion – an important event for a Catholic family – so I started attending school some afternoons and weekends. At such times, the school surroundings were lonely and juvenile gangs lurked around waiting for unwary and vulnerable people to assault them, usually using knives and blades, but sometimes with firearms as well.

After escaping a couple of mugging attempts, it was only a matter of time before luck was no longer on my side. I have to say that I was not an easy prey since, at the slightest hint of being about to be approached by robbers, my instinctive reaction was to run as fast as I could; something that worked for me on other occasions, though it is well known that many people earned punishment from their assailants, who do not appreciate escape or resistance attempts. To be threatened with a knife by teenagers, almost always underage, who manifested the effects of drugs, was for some people one more annoyance of the day to day, but for me, who had grown so oblivious to the rampant insecurity of most Colombian cities, it meant the transformation of the world into a hostile and dangerous place.

Suddenly, evil and crime were no longer scenes on television or stories told by others but the reality in which I lived every day. Several of my classmates boasted of belonging to gangs, of being muggers, or of having “poked” – a Colombian euphemism for stabbing – at some enemy. The bullies didn’t just, as they do in the movies, push their victims and hit them in the stomach, they often frightened them with knives and on more than one occasion I saw paramedics take badly injured students out of school.

Surviving high school meant having to team up with some upper class guardian and avoiding falling into the dislike of a “bad guy”. The whole situation was hopeless for me. The panic caused by evil and abuse overcame any hint of bravery I might have had, and the truth is that the last five years of high school were mostly a real ordeal between my effort to remain invisible at school and the feeling of being invisible to my dad at home, as our relationship during those years became rather distant. My favorite place to be was my room, where reading, music and fantasies were in charge of giving color and meaning to my life.

Courage

My fears were a topic rarely discussed. I remember mentioning it to my dad, who by the way had already shared with us many of the stories I told in the first chapter of this book, and this made me admire him as a brave man, from whom I could perhaps learn to be less of a coward. I do not remember well his answer, but I know that it had the practical style of the reasons that my parents learned to accept: The important thing is not to think about all that stuff too much, not to show fear and to be careful. There was no motivational talk alla “you have the strength within you” or anything like that, nor was there any money to allow me to change schools to a higher status or to pay for private transportation, but I do believe that this conversation could have been one of the reasons why my parents enrolled me in karate classes and the Boy Scouts [2] of Colombia.

I have to say that while I don’t think either activity took away any of my fears or made me any braver, they were two of the most enjoyable experiences I had during those years. The karate class of just one hour per week was not enough to give me the slightest advantage for hand-to-hand combat, not to mention protection from street robberies, but it did give me the first opportunity to practice physical discipline, mysticism through ancestral knowledge and the art of concentration. The Boy Scouts also did their part in fostering discipline, concentration and mysticism in me; although not of a religious nature but a mysticism for ingenuity, service and authority.

With the Scouts I met young people who were curious about science and technology and eager to possess knives and blades to gain the respect of the troop, but not through fear as I had seen in my school, but through respect and hierarchy.

From my short time in the “State of Israel” Scout company, I particularly remember one of the many tragic stories that urban violence has written in Colombia. The husband of the coordinator of the company to which I belonged had also been an enthusiast of the Scout movement and coordinator of a large group of girl and boy scouts. One day, while he was with his troop camping in one of the eastern mountains of Bogotá, high up in the National Park, the scout group, which was learning how to tie knots, dig stakes and other survival skills in the wild, was attacked by a group of thugs with firearms. Regardless of the presence of children, the assailants stripped the group of money and valuables, during what must have been endless minutes of panic for those children. But not content with the loot, the assailants decided to sexually harass some of the girls in the herd. The coordinator of the group, faithful to his principles and responsibility with the minors, tried to prevent the attack, to which the assailants responded by opening fire on him, taking away his life in front of his pupils.

The events had taken place several years before I joined the Scout troop, but the story still had a profound impact on my impressionable mind: How could there be people in the world who would act with such evil, what must have been those minutes of terror like, as the criminals walked among the children, seizing them and threatening them with guns, what could have been the last thoughts of that good man who certainly did not imagine that when he left home in the morning, it would be the last time he would see his wife and children?

The images of that event that I did not witness but that I recreated in my mind based on the story I heard, have haunted me ever since and from time to time they reappear. Sometimes I feel as if the spirit of that man who was killed for his courage is asking me not to forget him, that he does not want his sacrifice to be in vain. I did not imagine that I would ever write his story, but here I am honoring his memory because it represents both what I desire and what I fear most: the courage to stand up against injustice towards the weak, and the prospect of leaving this world to the unconsciousness that plagues it.

At the edge of the night

My favorite place at home was my bedroom, but even there I could not completely insulate myself from the harsh reality of living in a poor neighborhood in a hostile city of a violent country. My room was on a second floor, with a view to the street and almost no sound insulation from it. Some nights, usually Friday or Saturday, my frail sleep was interrupted by cries for help coming from outside, sometimes also by gunfire and quite often by the sounds of drunken brawls. When this happened, depending on the severity of the episode, my reaction was to lie still in my bed, paralized by the cold of fear and visualizing in my mind the events that would correspond to the noises I was hearing.

My wife, who grew up in a popular neighborhood in the city of Medellín, tells me that she remembers that, during her teenage years, on more than one occasion she heard nearby shots from her room, but not from a revolver or gun, but from a rifle or machine gun, and that the next day, the story was not of a robbery or payback but of a massacre carried out just a few meters from her house. Ordinary crime has been substantially reduced in Colombia in recent years and experiences like these are not as frequent as they were during the 1990s, however, it would still take a lot of terror to hit bottom for Colombians to recognize that our country was on the verge of becoming a failed state, a narco-state in civil war that would have made the tragedies of Syria or Yemen pale in comparison.

All this was prophesied by Jaime Garzón, a courageous -and probably mad- humorist who dared to denounce the formation of paramilitary groups at the service of the far right, and the collusion of politicians and drug traffickers. Personifying a humble and candid shoe polisher, Jaime sat at the feet of the most famous and powerful people in the country and from there he would call them “chanda”, “cafre”, “delinquent”, “corrupt” and other names, with astute judgement, while throwing sharp criticisms and inquisitive questions at them. The interviewees would laugh nervously and try to answer without seeming to be cornered but what they did not know was that millions of spectators who waited for each appearance of Heriberto, the character created by Jaime, saw themselves reflected in that character and felt a little popular victory with each intellectual knock-out that he gave them.

Unfortunately, thoug not surprisingly, Jaime Garzón was murdered on August 13, 1999 while on his way to work at the radio station “Radionet”. It was the first assassination that touched my heart and I still remember that Friday morning when my mother broke into my room in distress with the news: “Jaime Garzón has just been murdered”. The sadness and anger felt as if it were a close friend. Some headlines said “Laughter was killed” and a news anchor said goodbye to the broadcast of the news that day by saying “… Good evening… Fucking country!

The death of Jaime Garzón was just the beginning of one of the darkest periods of Colombia, a new bloody chapter in the history of my country that seems to have the habit of inaugurating a new period of infamy with an assassination and a catastrophe: In 1948 the political violence began with the assassination of Jorge Eliecer Gaitán and the burning of the downtown of Bogotá, in 1985 the violence of the cartels began with the assassination of the minister of justice Rodrigo Lara Bonilla and the avalanche of Armero but I had to witness more closely the paramilitary violence that began with the death of Jaime Garzón and a devastating earthquake in the coffee-growing city of Armenia. With the new millennium, a new nightmare began in Colombia.