This post is also available in:

![]() Español

Español

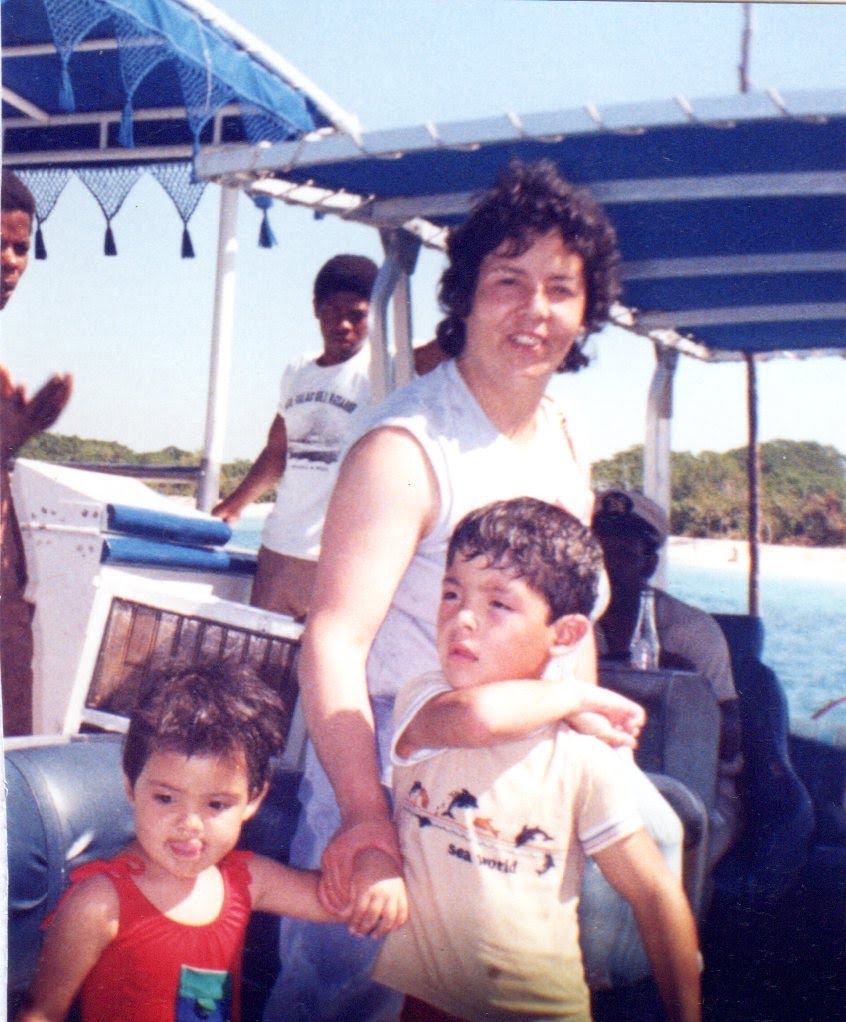

My mother, Julia Elena Rincón Martínez was born in a small colombian town called Fómeque, very close to Bogotá, 15 years later than my father. Hers was a less troubled time than the one my dad had to go through during his early years; unlike my father, my mother has better memories of her childhood, despite the hardships she and her family endured.

My mom’s story is also linked to the poverty of the 20th century in the rural side of Colombia, in a family marked by both their European and Indigenous heritages, but happily without the violence that my father witnessed in Paime. My grandmother Ana María Rosa Martínez was caucasian with blue eyes and my grandfather Luis Alfredo Rincón had the typical features of the Muisca people, original inhabitants of the Colombian territory. The Muiscas were the ancestral people of which I will speak in greater depth in a later chapter.

Peasant Ingenuity

Living in the countryside of Colombia in the second half of the twentieth century was a harsh business. At the time there were no paved roads between my mom’s country house and the closest town so traveling there took more than three hours walking or one hour and a half by horse. Despite this, my grandfather travelled there twice a week. Not only that but also, my grandparents organized expeditions of more than fifteen days of walking to go to Chiquinquira, a famous santuary located more than 200 km north of Fómeque.

Some of the stories that I most enjoy hearing from my mom, are those related to the ingenuity that the family had to use to meet basic needs. Things that today we take for granted and thanks to technology and science we can enjoy quickly and cheap. My grandparents were poor farmers who had to provide for their nine kids and they could not just go off to the convenience store and buy what they needed.

As matter of fact, my grandparents could only afford to pay cash for things that were absolutely impossible to grow, process, build or create with their own hands. An example of this that my mother remembers is making sleeping mats and reeds instead of mattresses, which the family did not even know about. They were made with the dried layers of stems extracted from banana palms that were grown near the house and rush, a plant that grew in the wetlands, using a loom as a guide.

The mattresses came to become a thing in the household when my mother’s childhood was long past. My grandmother was in charge of preparing the materials for making the mats and reeds, she cut the stems, peeled off their layers and cut them to the same length to let them dry. Then she added two rods at a certain distance from the center, and then coiled the stem layers to the rods, fixing them on place.

You might think that at least the rope used to tie the stem layers to the rods should have been bought from the market, but even that was homemade. My grandparents demarcated the farm with fique stalks and beautiful angel’s trumpet plants. This was not only decoration: fique is a monocotyledonous plant native to the Andean regions of Colombia, similar to the agave plant, with leaves whose structure is formed by strong fiber threads [1].

My grandmother would trim the stalks, crush them with a shredder, wash the fiber and let it dry and then weave it into braids or ties of various gauges. The family used these fibers not only for the mats, but also as ropes, espadrilles, laces and anything else that had to be tied. Nowadays, if someone needs a new mattress, they just have to go to Amazon, choose one that fits their budget, wait a couple of days for it to arrive, and place it on their bed.

For my mother’s family, even some of the things that we currently consider to be the simplest and cheapest were a demanding task that required the participation of several people for several days to complete. An advantage of those times was that the garbage that the household generated was very little. Almost everything was biodegradable, although not always disposed as compost, instead, some things were oftern burned, thus reducing the eco-friendliness of the peasant life. Even so, life in the country was much less aggressive against the environment than our current lifestyle in the cities is.

All this self-sufficiency was not only the result of economic restrictions, but also the legacy of our Muisca ancestors. The grandparents’ house was made mainly of wood, adobe and rammed earth, similar to those used by native communities 750 years ago. There were also some dirt floors, a few were wooden and most roofs were made of zinc, which in the past would have been replaced by straw and mat.

Traditional naturopathic medicine

I have already mentioned the difficulty of moving to the municipal seat in the time of my grandparents. That, added to the precarious quality of the Colombian health system at the time (even today it is quite poor), made traditional naturopathic medicine the first option when it came to medical care. My grandmother was a walking vademecum who knew the most effective remedies to treat everything from stomachaches to scorpion stings. The house was always surrounded by aromatic and medicinal plants such as rue, chamomile, dandelion, plantain, absinthe, borage, fennel, aloe vera, thyme, eucalyptus, elderberry, willow and many others.

An interesting story regarding the medical abilities of my grandparents is that once, the owner of a neighboring farm, who was cleaning the pasture with his machete, accidentally severed the thumb of one of his hands. He came to my grandparents’ and asked for help. When my grandfather saw the injury, he calculated that the guillotined finger would not survive the long journey to the town, so he did not hesitate to look for a needle and thread, have everything sterilized and proceeded to sew it. The anguished neighbor insistently asked my grandfather “will it glue or not?” To everyone’s surprise, with time and care, the finger “glued” and although it completely lost mobility, it spared the poor man of a lifefime with minus one finger.

Likewise, the neighbors of the region used to look for my grandfather for castrating their male animals, remove tumors, sacrifice terminally ill animals and other veterinary tasks.

There was, as well, a long list of superstitions that supplemented either by means of placebo effect or still unknown physical effects, the medical arsenal of the farm. These superstitions included having children urinate on hot stones so they would stop wetting the bed, bathing with urine from the navel down to reduce fever, praying spells to cure from the “evil eye”, massaging children who herniated after falling or getting scared, and other practices recommended by close friends or herbalists.

The pantry

Most of the food that made up the menu at my grandparents’ house grew, wandered, walked, or swam on the farm. Most of the animal meat that the family consumed came from animals slaughtered and prepared at home. Even my grandfather’s veterinary activities helped with the pantry: when he castrated oxen, he kept the testicles for the family’s nutrition.

The food, specially, reflected the mix of indigenous and European traditions present at home. For example, my grandmother baked unleavened bread, using wheat bought in the town, she also made cornmeal bread from corn abundantly harvested on the farm, threshed, at first on the grinding stone, later with a manual mill and much later, on the town in a motorized mill.

A third flour used by my mother’s family was extracted from a tuber called achira. Its name comes from the Quechua word “Achuy” which means “sneeze”, but in the region it was more frequently known as “sagú”. This plant, which is scientifically called Canna Indica – not to be confused with Cannabis Indica – and barely known in North America as Indian shot, was domesticated by the Muiscas and in it they found a good source of starch and potassium [2] .

The eggs, dairy products and sweets that my mother and her siblings ate during their childhood were, of course, homemade as well. For those of us who live in the city, we only require the small ritual of visiting the nearest store when we want to indulge ourselves, but on the farm, it also involved the participation of several family members for several days. From the milking of the cows in the early morning, which was done just after releasing their calves from their night confinement, to the numerous tasks in the kitchen to produce butter, cheese, curd, yogurt or my favorite: piches.

The latter, whose official name, if it has one, I do not know, was the result of heating the curd that formed when the milk was left to rest for two days, the cream with which the butter was prepared was extracted and the remaining lumps were put on low heat, the whey it produced was squeezed out and the result was mixed with grated panela[3], which is an unrefined solid sugarcane extract. It was a real delicacy!

The natural juices, sorbets and sweets that they enjoyed, came from the many varieties of fruits that grew, either intentionally or as weeds on the farm. These included water apple, lulo, tamarillo, sweet granadilla, mountain papaya, pears, figs and cuacha, this one was a small purple berry that some trees on the farm produced once a year. My grandmother enjoyed treating visitors with these exquisite preparations.

The most common alcoholic beverages of the time were of course also home-made and ,again, demonstrated the confluence of European and Native American traditions. Guarapo, one of the most popular drinks, was a fermented sugar cane drink of Spanish origin (probably from the Canary Islands), which peasants drunk almost on a daily basis. Day laborers who worked in agricultural work were specially fond of this beverage. It was prepared with a tea of panela, the sugarcane extract I described previously and which happens to be on the most popular traditional drinks in Colombia.

The twist was that they fermented this tea with a special yeast known as “cunchos“, which used to grow on the last residues of the guarapo that remained in the barrel or carafe. This starch was used to ferment a new portion of guarapo. It is also the origin of the colloquial term “cuncho”, widely used in central Colombia, to refer to the last remains of any drink… or also to the youngest kid of the family. The guarapo could be left to ferment so much that you could actually get drunk with it.

The other typical alcoholic drink from my grandparents’ time was chicha. This was also of indigenous origin and the Spanish chroniclers already gave an account of it in their first chronicles of the conquest of Central and South America. It is prepared from cooked and ground corn, sweetened with panela and also fermented in barrel or cured squash. It is known that its use by the Muiscas was ceremonial and therefore, even in the days of my mother’s childhood, it was used on special occasions such as baptisms, weddings or village dances.

A curious fact about chicha is that its ancestral fermentation process involved the women of the community chewing cooked corn and then spitting it into the jar. It is said that the Spanish, already fond of chicha, were not enthusiastic about the ancestral spit, so they replaced it with the cunchos from guarapo. The ‘cunchos’, however, did not get to attain the flavor and ferment that the Muisca saliva produced[4] . In any case, chewed ferment did not make it into the 20th century, unlike the spirit of its almost ritual use as a tradition passed from mother to daughter, which still survives in some regions of central Colombia.

The last drink from the fermented triad, Masato, also had a very important place among beverages in my mother’s household. It was prepared with corn or rice flour. It was softer and thicker than chicha and guarapo and specially prepared for family parties, accompanied with shortbread, empanadas, snacks, cakes and bread.

Seed of community service

All of the above marked my mother’s life and therefore mine. However, what I consider the most important part of her legacy is the foundation of the precepts that have defined her life: The importance of education as an enabler of personal transformation, punctuality and the need to help those around us.

Despite the difficulties described and the limited practical application of much of the theoretical knowledge that was taught in schools, my grandparents were rigorous in their certainty that education would be the tool to insure the future of their nine children. All of them received primary education, which, despite being free and easily accessible, just an hour’s walk away, was not widely used by a large part of the peasant community.

My grandparents believed that knowing how to read, write and perform basic mathematical operations was essential to prevent their children from being marginalized by society. My grandfather, who barely attended the third year of primary school, was a great self-taught all his life. He was in charge of providing for the family and ensuring that his children studied, so much so, that he sent them knowing how to read and write to school. He was the one watching for the children’s homeworks completion. He always said that studying was the only valuable inheritance that he was going to be able to leavevwhen he died.

Secondary education was more difficult to access because to obtain it, you had to travel to the town, which was, as I mentioned earlier, 3 and a half hours away on foot, that is, when the weather was good or roughly half that if the route was done on horseback. High school was not free, but my grandparents contemplated the possibility that all their children would finish their studies – if they so wished.

For my mother, who is one of the three youngest kids in the family, the situation was already more favorable than for her older brothers and thus she was able to study at the boarding school of the Presentation in Fómeque, partly thanks to the ability and political friends of my grandfather to get aid such as full or partial scholarships.

My mom arrived in boarding school as a teenager in the second half of the sixties, oblivious to the cultural and social transformation that occurred in the cities and willing to honor the effort that meant for my grandparents to provide six additional years of academic training. Thus she finished her training as a Higher Normalist in the school of the Presentation of Ubaté.

My grandfather, despite not having completed formal studies, stood out for his culture and knowledge. The inhabitants of the village came to him to seek advice, recommendations for agricultural trades or to resolve conflicts of different kinds. They also visited him to get haircuts, which he apparently did with great talent. My grandmother, despite the heavy work of the week, used Sunday afternoons to teach the catechism “of Father Astete” to the women of the village. I am still impressed by the humility with which my grandmother gave up her own resources and possessions to help others. On one rare occasion when she had a somewhat significant amount of money of her own, she used it to contribute in the formation of a nephew of hers as a priest. Now I see that same generosity, living on in my mom.

In my grandparents’ house there were events that were fondly remembered by my mother; This is the case of the celebration of the feast of Saint Paul and Christmas, occasions in which my grandmother used to prepare delicious delicacies for the family and to share with relatives and people in need of the region. My mother loved to carry out the mission of delivering the food. Her family also frequently held community meals in which the neighbors of the village were invited to share food, a fine cup of chicha, sometimes a religious service and cultural activities such as readings, games, dancing and singing under the light of a kerosene lamp.

Thanks to an environment as exemplary in service as it was strict in academics, most of my grandparents’ children became community leaders. My aunt Laura Rincón, dedicated her life to serving others through her offices as a religious of the Presentation. My uncles Alicia and Álvaro joined the Agrarian Peasant Youths and became representatives of the Colombian peasantry before the UN; leaders in the process of academic formation of the village and coordinators of cultural activities in the municipality. On the other hand, Luis, Rosa, Otilia and my mother would find their vocation in teaching.

After the death of my grandmother, my mother and her siblings agreed to gather annually around my grandfather, having encounters in which the patriarch would enjoy spending a few days with the entire family, in some cases above 40 people at once. From these encounters, one of the things that I remember the most were the a cappella choirs of popular songs such as “Matemos el gallo” (let’s kill the roster) or “La bella primavera” (the beautiful spring), which were sung like a canon of two or three voices, and of course the feasts, especially when the gatherings took place at my grandfather’s countryhouse.

The “teacher” Julia

My mother belongs to that special breed of educators who are truly passionate about their craft. She did not limit herself to just imparting knowledge, but always committed to the integral formation of her students. Since my mom’s graduation as a normal-school teacher, she began a career of more than 40 years training girls and boys in knowledge as important as reading, maths and science, but with special effort, inspiring her students in the importance of being creative, honorable, respectful, witty, curious and punctual. Her personal jargon was made up with expressions such as “you have to be a good student and an excellent person”, “put yourself in the shoes of the other”, “the problem is already there, let’s find a solution now” and “you cannot demand from students what as teachers we are not willing to give”, somehting she often reminded her fellow colleagues.

My mom’s mother-like teaching approach stood out in her concern for the students’ family problems and her focus on inspiring values rather than filling heads with knowledge. She also used to hug and comfort her students when they faced moments of sadness, and eventually even fixed a child’s uniform or hairdo just like she would do with her own kids.

During her entire teaching career, my mother only worked in the city of Bogotá. She, just like my father in his early days as a teacher, was first assigned to a school located in a marginal neighborhood with vulnerable population. My mom started working in January 1975, at the Van Huden district school in Fontibón HB, a populous neighborhood near the airport Eldorado. The school was soo poor that she had to use an abandoned bus in a flooded lot as a classroom. There, she had to carry in her arms the first grade students who wanted to go to the bathroom, to take a break or to return to their homes at the end of the day. My mom endured these inconveniences at work for a whole year, before she managed to get transferred to a school near her home.

As I said before, despite the poverty in which my mother grew up, she did not have to live the violent dramas of twentieth-century Colombia, which my father knew firsthand since his childhood. However, my mom had to face that same violence through the eyes of her little students the worst miseries of the human being. Some of those kids suffered situations that were then, and are still today, mostly experienced in the shadows of marginality and poverty, far from the reflectors of the media and only recorded as statistics: child abuse, malnutrition, sexual abuse, drug addiction and exploitation among other nightmares that no children should live anywhere,.

Despite all this, teaching represented an enormous satisfaction for my mother. Many of her students, particularly those who she was able to accompany during their five years of primary basic education, reached secondary school with outstanding skills in reading, writing and mathematics. Among them, my mom remembers more fondly those kids who managed to overcome learning and emotional challenges. For them, I am sure that my mother was an important emotional support and in many cases, a maternal figure. I know this because I was her student in my third year of primary school and I remember how my classmates did not notice a differential treatment from “teacher Julia” towards me, not because my mother treated me as a stranger, but because she treated the others almost as though they were her own kids.

Life companion

One of the many stories that my mother accrued during over 40 years working as a teacher, stands out from her recollections. It happened during the nineties while she worked in a small school in the poor neighborhood of “Las Colinas”. It was about a beautiful girl with blond hair that my mom had as a first grade student. My mom does not remember her name, but she does remember that she was an excellent student but interestingly, the little girl was very quiet, always attached to her brother and during breaks, my mom remembers that the girl never played with other kids, but instead, she usually remained motionless and emotionless, with her hands behind her back, leaning against the wall.

The school teachers learned that the girl’s mother was under house arrest after being captured and sentenced for assault and personal injury. The woman belonged to a gang that attracted unsuspecting male victims in bars and clubs of the city, then drugged them with burundanga, striped them of their personal possessions and abandoned them, sometimes to their death from overdose.

The gir’s father was also convicted for other crimes, but he was paying his sentence in prison, for which the children remained for long periods under the care of an old man who lived nearby everytime the mother violated her home arrest and left for days, doing who knows what.

The poor girl’s distant and melancholic attitude raised the suspicions of my mother, who sensed that there was something more serious than the parental absence in the little girl’s story. Her explanations and those of her brother did not leave my mom comptempt. My mom concern grew as the school team was not able to clarify the situation, so she referred the case to the orientation and pedagogical counseling team of the institution, made up of specialists in psychology, social work and pedagogy. They were immediately very interested in the case and designed a very careful strategy to find out, through games, conversations and other techniques, what was tormenting the little girl.

The plan paid off and so they confirmed that the girl had been a recurrent victim of rape by her own father. Her short life had been a hell of neglect, abuse, and mistrust, where the only stronghold he could hold onto was her brother. The counselors who dealt with the case taught my mother how to handle post-traumatic stress cases like this one, to gain her confidence and understand her fluctuating moods.

With the joint efforts of my mother and the group of professionals, the girl was, little by little, integrated into the group and began to participate in the activities with the other children and, most importantly, started to play and laugh now and then. Later on, she was withdrawn from school to go live with her maternal grandmother in the city of Villavicencio and my mother never heard from her again. However, her memory would remain engraved in the heart of my mom, who understood that the priority of her teaching work would not be to impart knowledge but to be attentive to cases like this one and to provide whatever help was within her reach. In her own words, she decided to become for her students, much more than a teacher. From now on, she would be a “life companion” for them.

My mother become particularly invested on children who showed disinterest, indiscipline or emotional problems and in more than a few occasions, she managed to become the decisive factor to ‘straighten out’ the lives of children who, perhaps, otherwise would have ended up in the clutches of crime, drug addiction, prostitution or suicide.

The New Educator

The socio-political environment of the late seventies in Colombia was highly polarized and, as I have previously noted, the teachers’ union was at the spearhead of the revolutionary ideological struggle. My mother, who did not identify herself with any existing political party, shared some socialist ideals of the time, particularly in relation to the equitable distribution of public goods and the state responsibility for the satisfaction of the basic needs of the population. Because of this, she accepted an invitation to participate in a left-wing study group, in which several enthusiasts met to discuss what the role of the public teacher should be in the context of the conjunctural moment and eventually under a future socialist government.

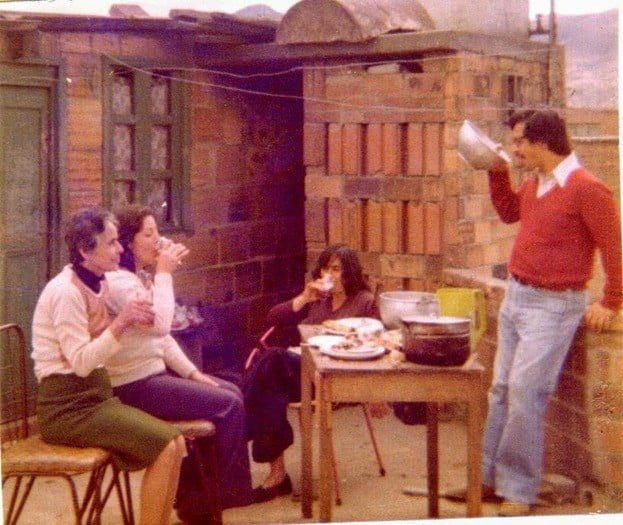

The study group was called “The New Educator” and its participants spent long hours discussing about the revolutionary experiences of Cuba, Nicaragua or El Salvador and the role that educators played in those processes. They also debated on best ideological scheme to be applied in Colombia and studied the educational models outlined by León Trotsky, José Martí and Quintín Lame. The study group members were also given tasks that sometimes bordered on the subversive, such as distributing pamphlets or painting walls with revolutionary messages. Be that as it may, “The New Educator” was never really more than a pretext for young professionals to socialize and interact with people who related to their own ideals. Hence, with some frequency, the he group scheduled social events where music and drinks, and not politics, were the main protagonists.

It was at one of these parties, at her sister’s house, that my mother fell in love with my father. Without knowing it, the leftist group would be the point of convergence that united the stories of two peasant kids who came to the big city to dedicate their lives to the education of childhood in a country of injustice and violence, but also of mysticism and big dreams.

My mother, was undoubtedly captivated by the handsomeness and eloquence of the bearded teacher Ávila, but what really captured her interest was a small detail that many men in my dad’s place would have been careful to hide: In the middle of the lively dance that they were enjoying, my father called Dolores, his mom. He told her that everything was fine and that he would stay a while longer but then he would immediately go home. The guy was almost 40 and yet he was so considerate, that he would stop dancing with a beautiful woman to keep his mom from worrying!

I’m sure my father would never have guessed that it was that short call to his mother what stole my mother’s heart, hadn’t she confessed it. Yes, Octavio had put him on the right path to get to that reunion, but my grandmother Dolores, had put him on the right path to reach my mother’s heart. Thank you grandma!

[1] Chacón-Patiño, Martha L., Cristian Blanco-Tirado, Juan P. Hinestroza, and Marianny Y. Combariza. “Biocomposite of Nanostructured MnO2 and Fique Fibers for Efficient Dye Degradation.” Green Chemistry 15, no. 10 (September 24, 2013): 2920-28. https://doi.org/10.1039/C3GC40911B .

[2] Cultivariable.com. “Growing Achira.” Cultivariable (blog). Accessed February 28, 2019. https://www.cultivariable.com/instructions/andean-roots-tubers/how-to-grow-achira/ .

[3] Unrefined sugar obtained from sugar cane, which is sold in compact loaves of rectangular, round or prismatic shape, depending on the region where it is produced.

[4] Lamb, “GUARAPO: THE DRINK OF THE COLOMBIAN PEOPLE.”