Last updated on 2020-10-03

This post is also available in:

![]() Español

Español

It is with great emotion that I want to share with you the first chapter of the story of my spiritual journey, which I wrote more than a year ago. This is something very important for me because this story encompasses, on the one hand, the experiences that my Father, like millions of poor children and young people in Colombia, had to face in the long conflict that is bleeding the country.

On the other hand, it reflects the socio-political changes of the mid-20th century and many of the circumstances that marked my spiritual path, even before my birth.

I hope you enjoy this story and share your comments with me.

With love, for you dad

Víctor Manuel Ávila, my father, is the youngest of nine siblings. He was born in Paime, a small town in the Colombian department of Cundinamarca, 130 kilometers north of Bogotá and there he lived his childhood in a turbulent period in the history of Colombia, a prelude to what would become known as the time of “La Violencia”. which took place between 1948 and 1958.

There is no certainty about the exact circumstances that originated this bloody history in my country, but itis commonly related to a period of political and rivalries and class-interset clashes between the liberal and conservative parties of Colombia. The government of the day fiercely challenged the opposition using fiery speeches, provoking responses such as the organization of guerrilla movements created to defend the leftist population from the corrupt military and government-backed parimilitay groups . The clashes that took place during those years were the seed that caused more than 300,000 deaths, more than 8,000 disappearances and some 7.6 million victims in the posterior 55 years of armed conflict[1] .

My grandfather, Rafael Jiménez Suárez, was a doctor and once mayor of Paime for the liberal party. After being lost for a few days, he appeared lifeless before my father turned 4, presumably drowned when crossing the Mancipá River, which separates the towns of Tudela and Cuatro Caminos. towns near the municipality where he and my dad lived. It is believed, nonetheless, that he was actually murdered because of his affiliation with the liberal party.

In addition to poverty that most peasants endured during the first half of the 20th century, my father also had to deal with the anxiety, caused by the persecution that the family was subjected to due to my grandfather’s political activities.

My dad was afraid of being attacked by the ‘chulavitas’, the paramilitary gtroups associated with the conservative party, who roamed the country roads of the region that my dad had to travel to run errands for my grandmother. Many times, these criminals threatened to take the town, something that caused fear and anguish to its inhabitants. They feared for their lives and their property. Massacres executed by the chulavitas were not infrequent at all in the countryside, and in some occasions, my father had to witness first-hand the arrival of peasants in the village carrying the severed and tortured bodies of their relatives or neighbors.

The violence touched the lives of most people living in the rural part of Colombia, but more viciously in some regions. The animosity that existed between liberals and conservatives was aggraviated by corruption, provocative speeches and occasionally even bare-knuckled fights between individuals from the highest social classes. The politicians from boths sides made an habit of spreading hatred and fear to the people. For this, conservatives in particular enjoyed the collaboration of some priests who used their pulpits to condemn Liberals to the fire of hell. In rural communities, this resentment translated into massacres, house arsons, rape, and other brutal actions.

When my dad was very young, says my father, he heard the story of a pregnant liberal woman, whose husband cut her belly open and extracted her fetus before beheading him. Such brutality just because he believed that in his absence, his wife had an affair with a conservative: “God forbid another fucking conservative is born”, he would have said as an epilogue to the macabre act.

No one, if poor, was safe from violence. The bandits of both parties, prodded by their leaders, remained eager for revenge, so it was enough that the victims were pointed out by someone they knew to warrant them a death sentence. In some case, simply wearing clothes of the wrong color could be enough excuse to be executed.

After my granfather’s death, no one in my dad’s family was involved in politics, but their relationship with a former liberal mayor, made them susceptible to hostility and persecution by the conservatives. This motivated my grandmother to give her children her last name and not her husband’s. This is the reason why my family name is Ávila and not Jiménez.

Upon the death of her husband, my grandmother was left without a steady income so she sold the medical books and instruments that he left. Once the family funds ran out, the Ávila family went to live in Tudela, a small village near Paime, on a small farm that my grandmother bought, thanks to a bank loan. Unfortunately the violence there was even more brutal. Mules frequently arrived with the impaled corpses of peasants tied to their backs.

The courage of two kids

A childhood event that deeply scared my father for life, happened when he was only eight or nine years old, in those years of atrocious struggles between liberals and conservatives in Tudela. The conservative government in office became alert by the growing organization of the “cachiporros”, As they called the liberal version of the “chulavitas”, which had been consolidating in the north of the department of Cundinamarca, in the area made up of the towns of Yacopí, Topaipí, Caparrapí and Tudela. In order to “pacify” the region, the government sent a fierce lieutenant from the army that my father remembers as “Lieutenant Guerra”. To achieve this goal, Guerra had been assigned a small contingent of soldiers, clearly insufficient to fulfill the task, that is, had the infamous lieutenant not formed his own paramilitary army with dozens of peasants, whom he himself trained to torture and kill. in the wildest way.

An acquaintance of my father whose last name was Rocha, was among the irregular members of Lieutenant Guerra’s squad. He told my dad about the methods they used to kill “cachiporros“, using mainly machetes as a tools of justice. Guerra and his men lashed the region for months looking for informants, torturing prisoners and using other violent tactics to find the names of the peasants who secretly made up the liberal self-defense gangs.

One day, just before dark, Lieutenant Guerra arrived in Tudela with his group, taking with them a herd of cattle, horses, and mules that they had stolen from the farms they had passed through. The lieutenant gave the order to find a place where his animals could feed and drink, before continuing their journey.

The next morning, when the crew was preparing to go on their way, the lieutenant took an inventory of their animals and noticed that one mule was missing. A few soldiers set off to look for the animal, but not being able to find it, they reported the news to Guerra, who, furious in the extreme, threatened the locals saying that if the mule did not appear, the inhabitants of the town would pay the affront.

He immediately order his soldiers to gather the local men in the central plaza and bring ropes from the town warehouses. They returned accompanied by dozens of men who were left standing in the square. Terrified, they heard Guerra ordering his men to tie the villagers to each other by the neck. My father, because of his age, did not suffer such unworthy treatment, but several of his relatives, who had the misfortune of being in sight of the soldiers were not that lucky.

-“Either you tell me where the stolen mule is or I’ll take you all tied up walking from here to Villagómez ” shouted the lieutenant. As he did so, the soldiers pointed rifles and machine guns at the terrified inhabitants, who trembled at the possibility of the saddist military keeping his word. Villagomez was about 20 km away from there.

Guillermo, one of the brothers of my dad, found the courage to speak to the hateful lieutenant and asked him for permission to go with a friend, to look for the mule in a place that was difficult to access, where they knew that the animals used to get lost. Guerra agreed, not before warning them that if they were not successful, they would have to join the macabre human chain”.

Luckily, the boys found the lost animal and managed to free the unfairly detained neighbors. This would be, however, an ephemeral relief, since before leaving the town, the lieutenant took hold of some beautiful horses that belonged in-laws of one of my dad’s sisters and announced that he would take them to Villagómez where he would then leave them, unless someone volunteered to go with them and bring them back. Guillermo, the brave brother who had just achieved the liberation of the people, was not willing to risk the animals to get lost, so he again went to Lieutenant Guerra and told him that he and my father would go with them to return the horses.

My dad was bewildered with both the bravery of his brother and the fact that he had pushed him to be part of the scary understaking. But he looked up and trusted his brother, so the two kids got ready for the 20 kilometers hike, behind the evil retinue on horseback. A couple of hours away, on reaching the small town of Cuatrocaminos, Guerra divided the platoon into two groups: one would continue to Villagómez and the other would go to Paime, the town where my dad used to live. Considering that one of the family animals would end up in Paime and the others in Villagómez, Guillermo convinced my father to go by himself with the group that went to Paime, while he would take care of the others.

Courage does not mean being unafraid

My dad still remembers the mixture of fear and emotion that overwhelmed him when he found himself alone, following the group of ruthless murderers, and the courage he had that day to continue advancing not even knowing if Guerra would keep his word. Recruitment of children for armed struggle was a common practice back in the day and still continued into the 21st century by illegal armed groups in Colombia. Fortunately, this was not my father’s destiny, as he was able to return in triumph with the horse of his sister’s husband. Before reaching Tudela, he met his brother Guillermo, who looked imposing mounting a gleaming saddle on one of the horses that Guerra had taken. When my father asked him about the chair, he said: ” The lieutenant gave it to me for having the courage to go with them.”

When my father told me this story, I could tell how proud he felt for not having surrendered to his own fear and been able to overcome it to protect his family’s assets. The fear of human violence and the need to confront it to prevent injustice would be two very strong driving forces during his life.

The episodes narrated here, together with many others that he had to go through, became stormy nightmares that haunted him for the rest of his life. Often at night he had vivid dreams in which he yelled that he is going to be killed. Sometimes he dreams that fights with robbers or jumps out of the bed thinking that he’s wresting a vicious animal.

All his life he has had to live accompanied by fear, sometimes irrational, of dangers that lurk on every corner. I judge that this is because of the persecution that he and his family suffered during his childhood. Fear became an imprint of his personality. For many years, he assumed the role of protector and watchman of his loved ones, an arduous task that in a way, would take the joy away from his life, which has been for the most part, a far cry from the hardships of his childhood and instead full of love and well-being.

The courage to face violence, experienced in episodes like the one in the previous story, endowed my father with the ability to confront injustice despite fear. Something undoubtedly admirable but also dangerous, as would become evident several decades later when, then in his 70s, my dad resisted an armed robbery that he and my mom were victims of near their home, right after they had withdrawn a large sum of money from a bank. My father struggled with one of the assailants, trying to keep the jacket where he was carrying the money, like ignoring the fact that he was being targeted with a gun. The bandits managed to snatch the garment from his hand and opened fire during their flight, fortunately not injuring any of my parents.

It should be noted that many people in Colombia have lost their lives during experiences like this, so my parents were lucky to leave unharmed, at least physically, that day. For both of them this event represented a psychological trauma from which my mother quickly recovered, using her usual positivism, but for my father, the incident meant the materialization of those gloomy dreams of yesterday and the manifestation of a looming anxiety crisis. Those episodes cascaded later in a developing Parkinson’s disease, which has accompanied my father ever since.

It is neverless true that my father’s courage also saved our family on several occasions, not defending us from violent events like the ones he experienced, but using his willpower to overcome his own vices, such as the cigarette before my birth. He succesfully fought drinking when he noticed that it made him aggressive towards my mother, and the desire for “easy” money that stalked him and his relatives, and which ultimately led several of them to their deaths.

But let’s go back to the 40’s …

My father’s family lived in Tudela for five years because my grandmother decided to sell the farm she owned there and return to Paime, where she and her children, with the help of inmates from the municipal jail, built a small house. Paime, as described previously was a faily violent town, and raising children there meant living in constant anxiety. They frequently got heads-up of the imminent arrival of the ‘chulavitas’ in the town, so the women and children ran to hide and spent whole nights among the giant bamboo fields near the river. The men were in charge of guarding the entrances to the town, barely armed with their machetes and old shotguns.

………………………………………………………

Chucho the muleteer, the one who lives in the cane fields, told me

That some are killed for cons, and others for leftists

But what does it matter grandpa?, then what is it worth?

My old folks were so good, they did no harm to anyone

Only one thing I understand, that before God we are all equal.

Sa called “chieftains” appear in elections

They keep promising schools and bridges where there are no rivers

And the soul of the peasant is stained by the partisan color

So they learn to hate even who was their good neighbor

All for those bloody politicians by trade.

“Who are you fooling, grandfather” Traditional song of Colombian folklore.

Arnulfo Briceño

The bipartisan violence that was already overwhelming in much of the country, was about to get even worse. Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, liberal candidate for the presidency of the republic, was assasinated by a poor man named Juan Roa Sierra on April 9, 1948, in the corner of Avenida Jiménez with Carrera 7 in Bogotá. According to some theories, the assasination was commissioned by the CIA and supported by the conservative government of Mariano Ospina Pérez.

This event unleashed the anger of hundreds of Gaitán supporters, who quickly aprehended the assasin, who was allegedly mentally unwell. The man was lynched and dragged to the steps of the presidential palace. There the enraged followers of the fallen leader continued to congregate and, given the possibility of a popular uprising, the government of Ospina Pérez violently repressed the protests. The clash of protesters with the armed forces unleashed such chaos, that culminated with the looting and burning of most of the city center. These events would henceforth be known as “El Bogotazo” (The strike of Bogota).

Working child

Poverty reigned in my father’s home, because of this, he and his brothers had to resort to family and friends to procure food and other necessary goods. Despite this, my father remembers that his mother preserved the dignity that gave her the fact of having been married to a doctor and mayor of the town. My grandmother’s friends, were still among the most prominent in the region. -“Let us not show our poverty” used to say my grandmother, who took great care in good manners and personal neatness of her children.

The situation of both violence and poverty became unsustainable in Paime, so my grandmother made the decision to send my father to the home of a friend of hers who lived in Bogotá. Just like millions of peasants would have to do in subsequent decades, my father emigrated to the big city in 1949, one year after the assassination of Gaitan, so he was able to witness the ravages of the violence unleashed during El Bogotazo.

Living in Bogotá, my father was forced to take on whatever job he was capable of doing: delivering products in the market place, delivery boy in a butcher shop, assistant in a stationery store, caretaker of a dairy farm, storekeeper, telephone operator, and even construction worker. Back then it was common for underprivileged children to work alongside adults in heavy and sometimes dangerous activities, as long as they were strong enough to do them.

At that time, the center of Bogotá was inhabited mostly by hard-working and honest people, but in some areas, such as the one where my father lived, robberies, fights, the presence of prostitution and other problems of the most populous areas of a metropolis in formation. It was far from the best environment for a child, but the advice and values instilled by my grandmother, kept my dad away from criminal activities, not from alcohol and cigarettes, though, which from an early age captivated him and would become a constant test for my dad’s willpower for many years to come.

Despite the daily hustling, the economic situation of the family was not improving. Alipio, one of the older brothers, in a certain way the hero and closest friend of my father in Bogotá, decided to become one of the hundreds of smugglers who bring liquor, clothing and other products from Venezuela and this way get quick money. Smuggling, by the way, would be the first criminal activity of Pablo Escobar years later. The young Alipio already had the necessary contacts among customs officials and the tactics to smuggle all kinds of goods without being discovered, so he invited my father to partner with him on this activity. It is easy to guess that my father saw in the proposal a quick and effective way to get out of the hardships they were going through, At the same time, my dad thought he would enjoy an adventure with his admired brother, so he committed to participate in the project.

The plan however, never materialized. Leticia, one of my father’s sisters, together with her husband Octavio, came up with a plan to dissuade him from such foolishness. In order to enter Venezuela, my father had to have a military service certificate, which my dad did not have yet. Leticia and Octavio invited him to their house in Junín, Cundinamarca, with the excuse of helping him resolve his military situation before his trip to the neighboring country. My father gladly accepted the help and paid a visit to his sister to get the promised help.

When he arrived, he did indeed find a hand outstretched, but the offer was quite different: If my dad agreed to cancel his trip to Venezuela, my aunt and her husband would help him validate his primary studies and support him to apply for a scholarship at the town’s teacher training school for his secondary studies. they would also provide him with a roof, company and the necessary support for him to become a rural teacher. As if that were not enough, they would also help him in obtaining the military record without paying the compulsory military service, using their influential contacts.

My father could not refuse such a generous offer, so he wounded up living with Leticia, Octavio and their four daughters in Junín. There he completed the four years of secondary education he needed to become a rural teacher. Those were difficult years for a young man who was already used to working, hooking up, drinking and smoking as well as picking up a fight from time to time. My dad, however, lived up to the trust that Octavio and that of his sister have deposited upon him. For the joy of my grandmother, my father gave up on the idea of smuggling, kept his bad habits under control and devoted himself to his studies.

Being at the training school, my father found it very difficult to keep up with the strict rules imposed by the priests who ran the institution and to accept the authority of teachers who were only slightly older than himself. This caused troubles with one of them, who, inconveniently, was also interested in a young woman that my father frequented. One day, when my dad arrived at the school, after been absent without permission, my dad ran into the teacher who was waiting for him at the door.

The teacher did not hessitate telling my dad off and threatening him of having him expelled. A furious Victor confronted him not as a student but as an equal adult. For this, he was summoned by the school’s director, who reproached him for his actions, brought up the scholarship my dad had been given and suspended him for fifteen days. This incident almost ended up frustrating my dad career as a teacher.

Despite the ill-will of the priests who ruled the school and the teachers, my father had earned the respect and affection of his classmates who admired his frankness and spirit of solidarity. The students who my father taught during his teaching practices, respected and loved him. He developed talent and love for teaching and the ability both to listen and to advise people in need, so much so, that my father came to contemplate the possibility of becoming a priest himself. His idea was to exercise this way the service to the community and, probably, to do so better than those backward clergymen he had known. Some of whom proclaimed, for example, that no liberal could call himself a Christian. I probably inherited some of my dad’s original intention of helping others through spirituality.

Becoming a priest, instead of a teacher, would be another project that my father -fortunately would never carry out. Not because of the intercession of his mother or Octavio, his “guardian angels”, but because of the discrimination of the church towards the “natural”or bastard children. Since my father only carried my grandmother’s last name, his civil registry looked like that of many extramarital children, reason enough to be rejected as a seminarian. Looking back and knowing that my father had a great time in the company of the ladies, I dare to doubt much success in his eventual clerical apostolate.

The story of Tom Thumb

Along with the bitter political and social violence that has plagued my country for most of its history, sexual violence is the expression of terror that has been most vicious against women and children, particularly in the marginal areas of Colombia. At the beginning of his teaching career, my father faced this harsh reality through his students and learn to recognize the signs of such violence to help those who were abused and to stop the spread of the evil among the children themselves, who from victims were painfully becoming victimizers.

Such was the case of “Tom Thumb”, a little boy that my father taugth to during his first years of teaching at an institution called “El Amparo del Niño”, dedicated to training in arts and crafts in Girardot. The students were juvenile offenders captured in neighboring towns and one of the crimes that was most frequently charged to the minors that this center cared for was sexual abuse of other minors. Taking advantage of the anonymity provided by the vast forests surrounding the Magdalena River, many children who had been abused themselves by adults, ended up doing the same to even younger children whom the young rapists intercepted on the lonely roads in the area.

“Tom Thumb”, as everyone called the kid in this story, was one of the little ones who suffered from this scourge. Nevertheless, “Tom Thumb” was a lively and cheerful child whom everyone in “El Amparo” were very fond of. My father remembers this boy both for his joy and talent with music, as well as for the difficult experiences he suffered, which he saw as a sign of a sick society.

“Tom Thumb” was raped by other boys, barely older than him. As if this was not enough calamity, the poor boy was also infected with syphilis, a sexually transmitted disease. The infection had spread to his internal organs, causing kidney failure and other problems that put “Tom Thumb” on the brink of death. My father, along with other teachers, took care of the child for several days and nights, providing him with the necessary medicines and care until, happily, he made a full recovery.

The incident would, however, not be the last time that “Tom Thumb” had to slip from the clutches of death. During a walk to the Magdalena River, the teachers who were caring for the children, including my father, warned those who could not swim, to stay on the shore, away from the strong currents of the mighty river. “Tom Thumb” was one of the minors who did not know how to do swim and because of that, the teacher were alarmed when they could not find him on the river bank. They went in search of the boy and after long minutes of agonizing search, my dad finally managed to see the boy as he approached the shore, swimming clumsily, from the river inland.

My father helped him get ashore to compose himself and then ask him why he said he couldn’t swim. Tom Thumb’s answer was: -“I learned just now after José pushed me from that stone .” An incident with a humorous ending that could have been otherwise been tragic, shows the ruthless law of the jungle, which many children lived – and still live – in marginal areas of Colombia. Many stories like this also shaped in my father’s mind a sharp mistrust of human nature, which he considered prone to evil and debauchery. – “Think wrong and you’ll be right” was one of his most frequent sayings, especially when it came to sexual instincts.

This mistrust was not only towards other men but even towards himself and later on towards me, his son, too. For my dad, men were carriers of that “original sin” or seed of evil that could emerge at the slightest oversight. This mistrust would become much later a determinant of my spiritual path and some of the trials we had to face together, but that is another story.

Revolution

Failing to become a priest, which would have been a challenge anyway, my dad became a rural elementary school teacher in the midst of the political and cultural revolution of the 1960’s. These years of turmoil deserve a brief contextualization: At that time, Latin America had become an ideological battlefield of the cold war, where a struggle was fought between an oppressive and religious right-wing government and a left wing composed by a couple of leftist parties, the communist party, most of the labor unions an three revolutionary armed groups.

Just like most other western countries, Colombia has a representative democracy. Citizens go to the polls every four years and vote to elect a president who is the head of the State’s executive branch. Presidential candidates, for most of the 20th century, always belonged to the liberal (center-left) or conservative (right wing) party. Both fractions have been led since the beginning of the republic, by white men belonging to traditionally powerful families, usually landowners, descendants of the Spanish feudal lords and in practice, owners of most of the country since the times of the colony.

The Catholic Church firmly supported the political status quo, because it allowed the church to enjoy enormous power in politics, education, health and in society itself. In a country where by then 90% of the population identified themselves as Catholic, Apostolic, and Roman 1, this power was enough to ensure that the majority of citizens would not dare to challenge the ruling order.

Things, however, were about to change, thanks to the influence of the communist think thank, philosophers from Russia and China, but to a greater extent, thanks to the enthusiasm generated by the 1953 Cuban revolution. The expansion of communis excited many, even Catholic priests, such was case of the Spanish Domingo Laín and the Colombian priest Camilo Torres, one of the inspirers of liberation theology and author of the phrase “If Jesus were alive, he would be a guerrilla fighter”

The communist promise of equality and justice for the poor, plus the uprising of the oppressed – the proletariat – strongly resonated in the minds of the peasants who had left the countryside and suffered the severity of poverty and exclusion in the most deprived, poor and marginal neighborhoods of the big cities. Indigenous people and farmers, who, to a greater extent, suffered the word of the violence in the countryside, were also on the side of the guerrilla warfare.

The images of armed peasants entering triumphant in Havana, motivated hundreds of workers, students and community leaders to leave for the mountains and jungles of Colombia, to take up arms against the establishment. Between 1964 and 1967, three guerrilla groups were formed in Colombia: FARC [1] , ELN [2] and EPL [3] . The first of them supported by the Socialist Soviet Union, the second by Marxist Cuba and the third by Maoist China.

According to official history, the Cold War was a political and ideological tension in which not a single bullet was fired, but nothing could be further from the truth. Perhaps the Soviet Union and the United States never sent troops to die in a military confrontation, but both powers fueled countless armed struggles in the Middle East, Africa and Latin America, which produced rivers of blood that continue to flow to this day.

In Colombia, the guerrilla groups received training, weapons and money from the USSR and the military and paramilitary forces of the Colombian government obtained their resources from the taxpayers and the United States. In this context, leftist groups deployed their doctrine in the cities, attracting the most receptive population segments, such as the youth and the working class in universities and unions. While the extreme right used the church, the army and the secret police to neutralize everything that smelled like left, as we say in Colombia, “by hook or by crook.”

One of the guilds that showed the greatest sympathy and militancy around socialist precepts was that of official teachers. Private school teachers, on the other hand, were less combative or straight up loyal to their employers. Most public school teachers were well educated people from the least favored social classes. They were also well organized and willing to fight for the dignity of their job and of the educational community in general.

In 1963, with this complicated context as a background, my father was placed in a school in Bogotá. There he not only began his career as an educator, but also practiced another trade that he had found also rewarding, representing his co-workers in the District’s teachers union. The District Association of Educators (ADE) was one of the most belligerent unions in Colombia and as I said before, an organization that ideologically leaned strongly to the left.

Aside from teaching Maths, Social Sciences and other subjects, my father spent part of his day listening to the complaints and claims of his colleagues and represented them in the assemblies that the ADE held every month. The teachers also spent long hours between classes and after their meetings discussing the political affairs of the country, sometimes to the beat of the revolutionary chords of Silvio Rodríguez or “Ana & Jaime”. During those conversations, many of them professed their loyalty to the communist party. who struggled to gain any political representation, but others did not hesitate to express outright sympathy for some of the guerrilla groups that fought in the mountains of Colombia.

Having witnessed the harshness of violence in his native land, my father did not support violence as a means to achieve social justice, but the romantic image that the Cuban revolution projected on the Latin American left, influenced him to consider that if one wanted to overcome the resistance that the oligarchy exerted against the emancipation of the people, certain level of violence was inevitable. Even today, after having visited Cuba a couple of times, my father still thinks that, despite its shortcomings, Cuba is a more egalitarian and happy society than any capitalist Latin American country. In this I consider, that some reason indeed assists him.

Nonetheless, Colombia is not Cuba and after years of armed rebellion, none of the main three guerrilla groups (because there were yet other minor guerrillas), managed to destabilize the rule of the democratic system. The guerrillas also had already shown signs of corruption and excesses, in addition to other problems, that led to the decline of the guerrilla movement in the country. In fact, guerrilla-controlled territories became a collage of micro-states embedded in the map of Colombia, in which they adopted variants of communist and socialist schemes, while executing shady businesses such as drug trafficking, extortion, kidnapping and smuggling.

Despite his admiration for Cuba and his loyalty to the communist manifesto, my father refrained from supporting any armed rebel groups. This was, until the M-19 appeared. The April 19 Movement was a guerrilla that was born in the second half of the 70’s, that managed to obtain significant popular support in the cities, especially among the working middle class. Its main appeal, to a large extent, derived from its composition by intellectuals and its moderate approach to violence, something that ended in 1985, when the guerrilla carried out the military takeover of the Palace of Justice, an event that caused 98 deaths and that sealed the union between drug lords and guerrillas in Colombia2.

The M-19, or the “eme ” as the people affectionately called them. were also popular for symbolic heists, such as stealing milk trucks to distribute the product among the poor, and stealing the sword of the liberator Simón Bolívar from the museum that kept it[4]. The intention with this act, was proclaiming that the mission to free Colombia from oppression was now in the hands of the people3. These and other symbolic acts made them worthy of admiration from the poor of Colombia..

Many teachers, philosophers, students, and workers turned their lives around fighting for their ideals in the ranks of the guerrillas. Some of them did so by taking up arms in the mountains, but others stayed in the city as ideologues, recruiters, or assistants in the movement’s urban military actions. By 1976, my father was already a well-known leader in the district union and had participated in some political assemblies with the urban commands of the ELN and the M-19. At that time, near his 40th birthday and with no plans to start a family, my father thought that his vocation to help others would find a place by joining this revolutionary movement.

My dad finally got the invitation to join the guerrilla but he was aprehensive about making such a life-changing decision, so he decided to consult his beloved mentor Octavio González. Octavio had in fact, already been concerned about the frequent encounters that my dad had with a teacher who was a well-known M19 activist.

Octavio listened carefully to the explanations and arguments that my dad had prepared, but he was not willing to let my dad’s life derail. Not even with the excuse of helping to achieve the elusive social justice that the country badly needed. With very strong arguments, love and intelligence, Octavio manager to convince my dad not to attend that invitation.

Octavio had worked the same charm that he did 20 years earlier, to dissuade my father from becoming a smuggler on the border with Venezuela. With this, the revolutionary project of my dad came to an end. Perhaps Octavio brought up the many vices of the Russian, Chinese and Cuban revolutions, the excesses committed by the Latin American guerrillas or the contradictions between the romantic discourse of the communists and their actions. Anyway, my father gave up the idea of becoming a revolutionary.

Later that same year, my father met Julia Elena Rincón, my mother, who was at the time enthusiast and supporter of socialism. These ideas brought them together and their affinity in values and ideals made them promised to work as a couple to live and honor the ideals of the revolution and love… For the cause.

Thanks, Octavio!

[1] Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia

[2] National Liberation Army

[3] People’s Liberation Army

[4] Simón Bolívar was the commander of the troops that liberated Colombia and four other Latin American countries from the yoke of the Spanish crown in the early 19th century.

[5] National Commission for Reparation and Reconciliation (Colombia), ed. Enough already! Colombia, Memories of War and Dignity: General Report. Corrected second edition. Bogotá: National Center for Historical Memory of 2013.

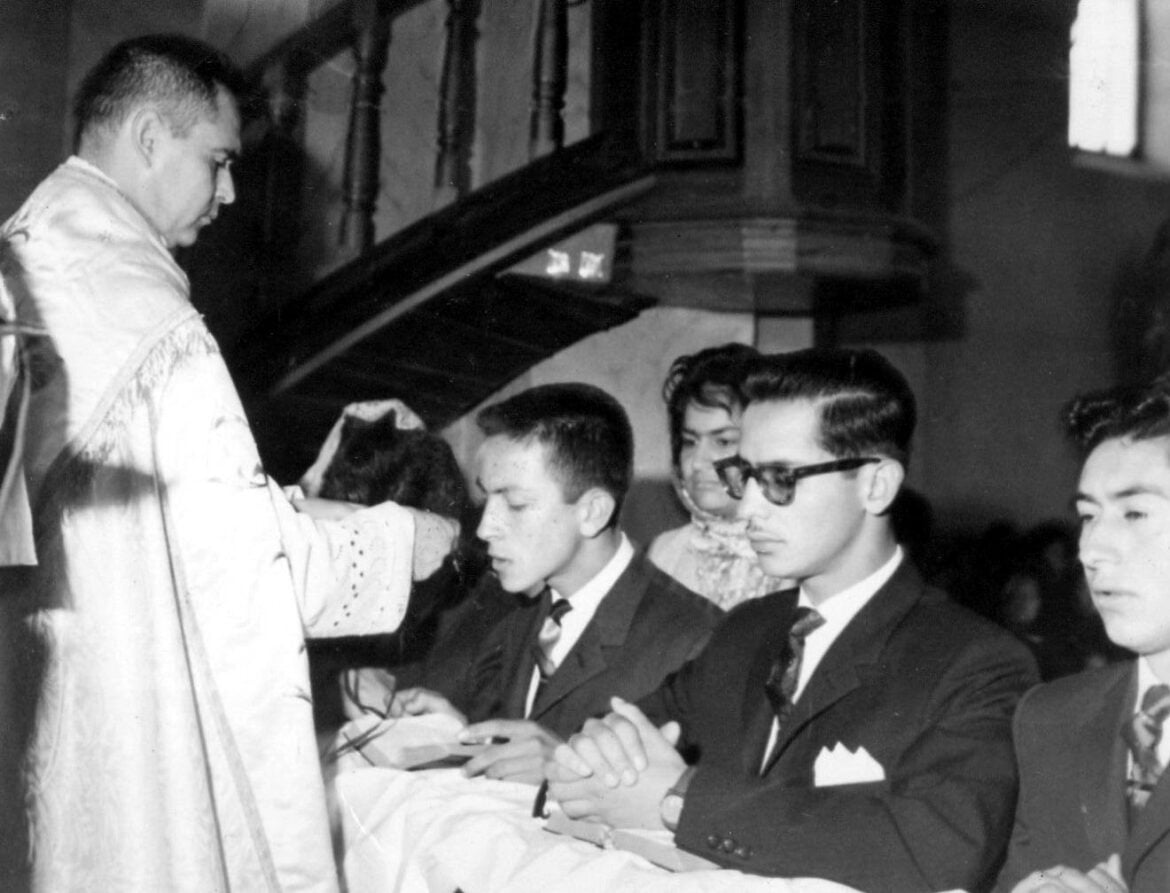

My dad’s first comunion

Photograph of my father’s permit to work as a child

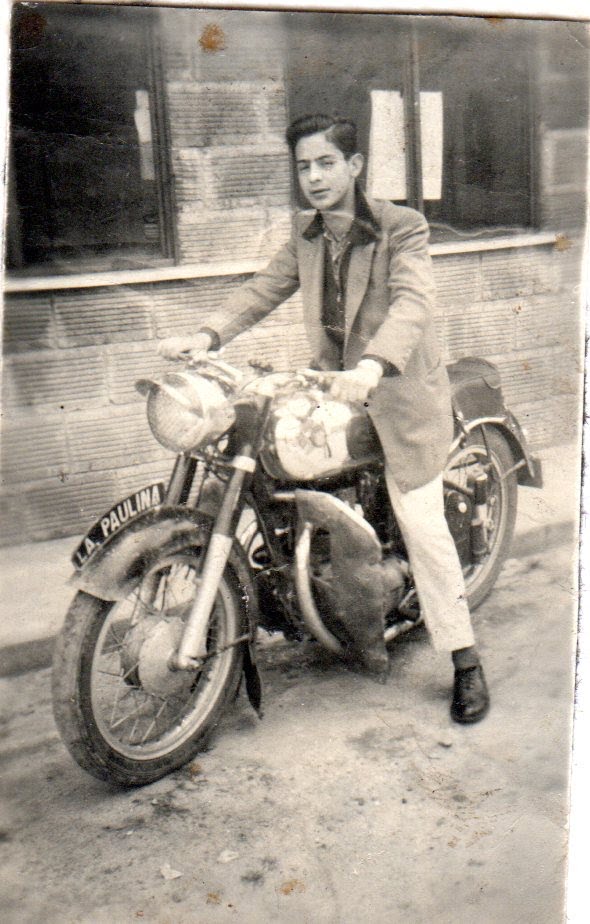

Paulina was the name of one of my sisters. My dad has never acknowledged that this was not a coincidence!

Photo from the teachers training school graduation mosaic

Mass before the graduation

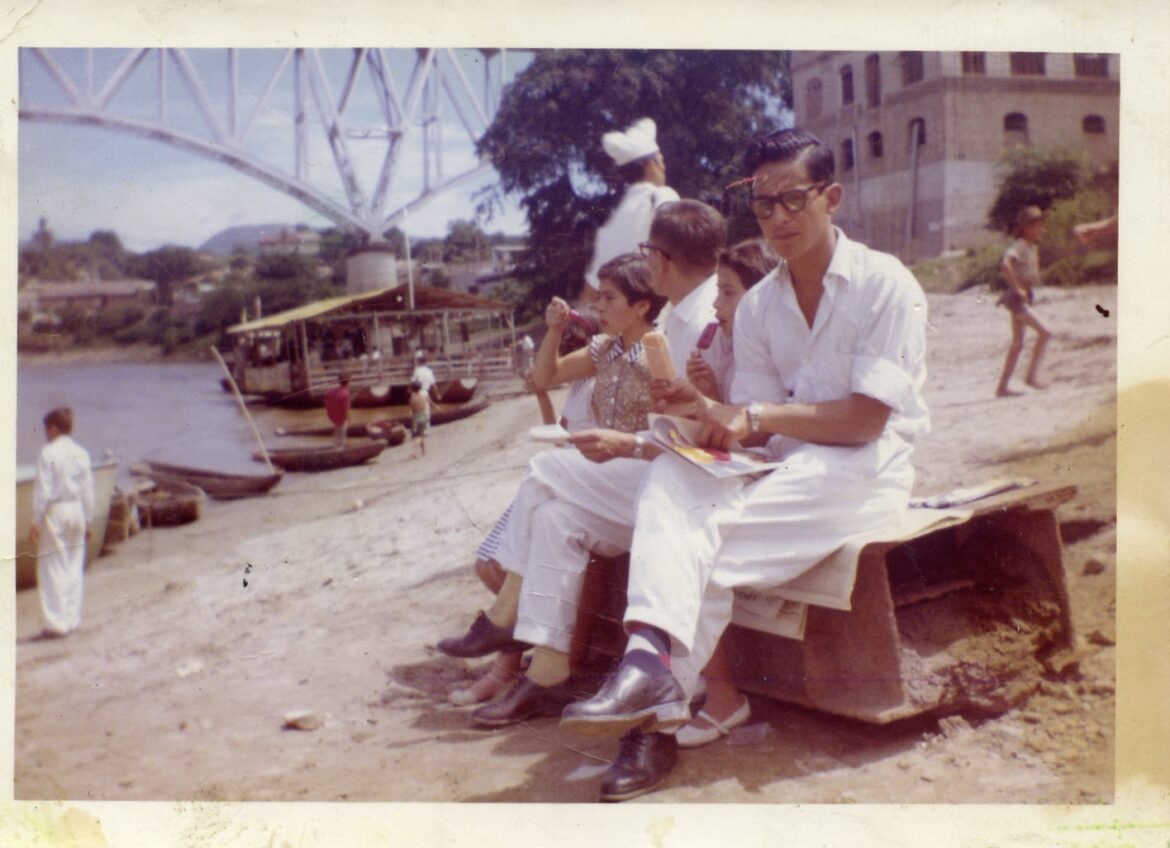

Working in Girardot as a teacher for the first time. In the years of “Tom Thumb”

The story about your father and your family is very powerful and emotional. It will make a great TV series or movie.

Thanks for sharing

A subscriber from Cyprus